Kiddushin, the section of Talmud that discusses marriage. How to acquire a wife. Aquire. This is a transaction, with uncomfortable comparisons to the process of buying a field. Or the other commercial activity that involves people - acquiring a slave. There is a lot of discussion about slaves in kiddushin, as there was in the tractate that discusses divorce. The notion of slavery has particular connotations today which might not be applicable to the type of servitude that the Talmud discusses. The master has obligations to look after the slave, in terms of food, lodging. And when the slave goes free it costs the master greatly in the gifts that they should give. Nevertheless this is a human relationship based on ownership, power and control.

and thus to marriage... after learning this mesechet it is very clear that the marriage ceremony that we do today is not the same as the process described in the Talmud. It has echoes, but it has changed. When that change happened, and how is another discussion. What struck me is that the parts that have remained have their source in this worldview where the wife is property. why do we still do kiddushin? (and kiddushin requires consent and understanding from the woman. I'm not sure that couples marrying today really understand the consequences of kiddushin, and give their consent to this arrangement.)

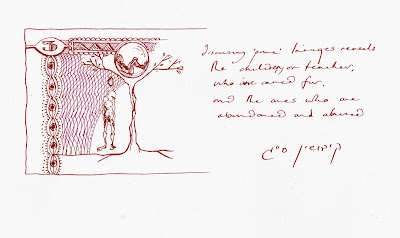

I decided, after the first daf, to use the form of banknote art to explore this tractate. It seemed to be the perfect vehicle to discuss marriage as transaction. And I had this nib with a pointed finger with which to draw. The extended finger is an echo of the bride's action to consent for the groom to give her a ring and thus agree to be brought. I was using that finger to give voice to my, very female, perspective on the, very male, discussions of how to buy a wife. (sadly, although not symbolically, that nib broke 3/4 the way through, and I had to finish it with a regular nib. no extended finger on the nib, although my finger was raised in other ways...)

farewell seder nashim

"sometimes it's hard to be a woman...." But Tammy Wynette was wrong, it has got nothing to do with loving just one man. But rather, it's been bloody hard to be a woman learning daf yomi, going through Seder Nashim and realising that what to do with women has been the subject of many many men's debates and conversations.

"sometimes it's hard to be a woman...." But Tammy Wynette was wrong, it has got nothing to do with loving just one man. But rather, it's been bloody hard to be a woman learning daf yomi, going through Seder Nashim and realising that what to do with women has been the subject of many many men's debates and conversations.

It's been a bumpy road that has given me much to mull over, and re-assess my relationship with Torah. But I have stuck with it, and if nothing else, that was something to celebrate. And so I made a siyyum with thoughtful, opinionated friends who let me rant and rage, sometimes bitterly, but also knowing that this is part of what it means to engage with our heritage. There are good bits, and there are bad bits. and it's not so simple to walk away. Or to gloss over the difficult sections. One friend asked me what kept me going... I don't really know. It's partly stubbornness now, and ego, curiosity, habit... I still get huge amounts of satisfaction and enjoyment from the intellectual exercise of learning, processing and drawing as a means of thinking and understanding. And ownership. By drawing each page of talmud means to take the text from the shelf of the beit midrash and have it enter my studio. It has now crossed over into my notebook, and the drawing allows me to own and 'tame' this text. To stop this project because the text is too difficult only silences my voice in this ever expanding conversation. And I am arrogant enough to want to assert my voice. And this is how I do it. With pencil, pen, watercolour, ink, embroidery thread etc (although I have not yet tackled a mesechet in embroidery. I am waiting for a fairly short one to do that challenge). Each medium pushes me to think and process differently, and each mesechet has it's own flavour, personality.

It's been a bumpy road that has given me much to mull over, and re-assess my relationship with Torah. But I have stuck with it, and if nothing else, that was something to celebrate. And so I made a siyyum with thoughtful, opinionated friends who let me rant and rage, sometimes bitterly, but also knowing that this is part of what it means to engage with our heritage. There are good bits, and there are bad bits. and it's not so simple to walk away. Or to gloss over the difficult sections. One friend asked me what kept me going... I don't really know. It's partly stubbornness now, and ego, curiosity, habit... I still get huge amounts of satisfaction and enjoyment from the intellectual exercise of learning, processing and drawing as a means of thinking and understanding. And ownership. By drawing each page of talmud means to take the text from the shelf of the beit midrash and have it enter my studio. It has now crossed over into my notebook, and the drawing allows me to own and 'tame' this text. To stop this project because the text is too difficult only silences my voice in this ever expanding conversation. And I am arrogant enough to want to assert my voice. And this is how I do it. With pencil, pen, watercolour, ink, embroidery thread etc (although I have not yet tackled a mesechet in embroidery. I am waiting for a fairly short one to do that challenge). Each medium pushes me to think and process differently, and each mesechet has it's own flavour, personality.

In kiddushin there have been a couple of observations about artisans and their relationship with their craftwork. An object that has been commissioned by another for a fee, will neverthless always be partially owned by the artisan, as they have put themselves into the work. Crafting with the hands takes devotion. It is precious work and time, and the artisan should not interrupt their concentration by standing and showing honour to the rabbis. I take from this, and I know that there are those who will disagree (but they would, wouldn't they...), to stay focused on my artwork and drawings, and stay true to that focus that is motivating me through this, and not to be concerned about showing deference to rabbis. Although they are welcome to join me on this artistic journey and be part of the conversation. (some of my best friends etc...)

In kiddushin there have been a couple of observations about artisans and their relationship with their craftwork. An object that has been commissioned by another for a fee, will neverthless always be partially owned by the artisan, as they have put themselves into the work. Crafting with the hands takes devotion. It is precious work and time, and the artisan should not interrupt their concentration by standing and showing honour to the rabbis. I take from this, and I know that there are those who will disagree (but they would, wouldn't they...), to stay focused on my artwork and drawings, and stay true to that focus that is motivating me through this, and not to be concerned about showing deference to rabbis. Although they are welcome to join me on this artistic journey and be part of the conversation. (some of my best friends etc...)

Another surprising little observation about craft is on the last page of kiddushin, where it discusses what would be an appropriate profession for a nice Jewish boy. Nothing demeaning, nothing where he would have to fraternise with women (God forbid!). Something clean and easy. R. Yehudah suggests embroidery. Sadly the discussion ends with extolling the long-lasting virtues of learning Torah as opposed to other trades. Although personally I would have welcomed a contemplation on the eternal benefits of learning cross-stitch.

Another surprising little observation about craft is on the last page of kiddushin, where it discusses what would be an appropriate profession for a nice Jewish boy. Nothing demeaning, nothing where he would have to fraternise with women (God forbid!). Something clean and easy. R. Yehudah suggests embroidery. Sadly the discussion ends with extolling the long-lasting virtues of learning Torah as opposed to other trades. Although personally I would have welcomed a contemplation on the eternal benefits of learning cross-stitch.

The journey of Seder Nashim has been tough going, beginning with Yevamot - the marriage of the widow of the childless man so that his name can be preserved, through Ketubot - the document of marriage spelling out the responsibilities to take care of the wife; Nedarim - vows, now that you have a wife you are responsible for her words and can nullify them; Nazir - the vow of a Nazarite to abstain from haircuts, wine, contact with the dead. a vow made out of disgust of seeing a suspected adulterous woman; Sotah - what to do with the woman who is suspected of adultery; Gittin - divorce her! and finally Kiddushin - marry her... Looking back through this arc, I realise that Seder Nashim has nothing to do with women. It's all about the boy. Getting a son and heir. For which a man needs a woman. On the last page of kiddushin a comment from Rebbe sums it up, "it is impossible for the world to exist without males and females, yet fortunate is he whose children are males, and woe is he whose children are females."

The journey of Seder Nashim has been tough going, beginning with Yevamot - the marriage of the widow of the childless man so that his name can be preserved, through Ketubot - the document of marriage spelling out the responsibilities to take care of the wife; Nedarim - vows, now that you have a wife you are responsible for her words and can nullify them; Nazir - the vow of a Nazarite to abstain from haircuts, wine, contact with the dead. a vow made out of disgust of seeing a suspected adulterous woman; Sotah - what to do with the woman who is suspected of adultery; Gittin - divorce her! and finally Kiddushin - marry her... Looking back through this arc, I realise that Seder Nashim has nothing to do with women. It's all about the boy. Getting a son and heir. For which a man needs a woman. On the last page of kiddushin a comment from Rebbe sums it up, "it is impossible for the world to exist without males and females, yet fortunate is he whose children are males, and woe is he whose children are females."

Women are a problem. but a necessity. So here is how to deal with all the possible problems of having to have a woman give birth to your son, to whom you should teach Torah.

Women are a problem. but a necessity. So here is how to deal with all the possible problems of having to have a woman give birth to your son, to whom you should teach Torah.

Bring on Nezikin. I want to learn how to deal with damages. There is much repair needed. I, and my relationship with Torah, God, Rabbis, has suffered much damage from this chauvinist attitude. woe to those with daughters to whom you have created this shit to deal with.